A few introductory thoughts…

Ron Friedman has died. It’s sad, because he wrote some important teleplays and screenplays that mean a lot to a generation of kids. But that sadness is lessened because he was 93. I know lots of people who didn’t make it that far! Congrats on a long life, Ron.

In 2013, Ron Friedman reached out to me on LinkedIn. This was a pleasant surprise, because it’s always the other way around. I email or message people to ask them for interviews for my G.I. Joe history book! Here was an important person who somehow found me. “Since I created the franchise for television by writing the five-part pilot miniseries that sold the show, and then wrote two more five-parters, the last of which was originally intended to be released as a feature film, maybe we should get to know one another,” he wrote. This is true, Friedman wrote G.I. Joe’s original 1983 “MASS Device” miniseries, and the 1984 “Weather Dominator” follow-up, plus the 1985 “Pyramid of Darkness” 5-parter. Indeed, Ron Friedman wrote the first 15 episodes of G.I. Joe. And of course there is G.I. Joe: The Movie.

But I didn’t need to get to know Friedman, despite his kind outreach, because we had in fact done an interview in 2007! I reminded him of that, and we both had a good email chuckle. I’ve spoken to so many people I sometimes get mixed up who did what, or which person lent me a photograph, or to whom I sent a follow-up question, especially since I have two different email addresses, and Facebook Messenger isn’t as easy to search as email.

Just earlier this year Friedman and I were emailing a bit, me trying to get a photograph of him to put in my book. (I didn’t get the one I wanted, and will try to reach out to other people when a little more time passes.) I very much appreciated how willing to talk and type he was at age 93, much less look for a photograph, and attach it to an email, and all before and after packing up and moving. He was patient and kind. I don’t think I’ll want to be on my computer much if I get to that age! And now I think about the long sweep of Friedman’s impressive career, so I’ve written a few paragraphs and pulled out some sections from our phone interview.

When I think of Ron Friedman…

Three things strike me about Friedman. First was his confidence. Some might describe that as cockiness. Perhaps he had earned it for his many accomplishments. Look at that phrase above, “I created the franchise for television.” True, Friedman did write the earliest episodes, so our conception of who the Joe characters are in animation comes from his teleplays. The tone is his, and I have so much to say about that tone – the light way in which Joe and Cobra alike use resources and whip up technology. For example, Steeler and Short-Fuze building a satellite in their spare time between scenes, one that launches into space right in front of them, from Joe HQ, with the push of a button! But also Destro’s cool calculations, Cobra Commander’s authentic cruelty, their outbursts at each other. My 6-year old brain lit up when Destro crushed CC’s baton with his hand and usurped leadership of Cobra! Also great, the easy camaraderie of the Joes. The global scale of G.I. Joe is worth mentioning, and all the vivid and evocative locations – the Island of No Return, the Devil’s Cauldron, the arctic Roof of the World.

But that word, “create” catches my attention. Animation is collaborative. I don’t want to diminish Friedman’s enormous contribution to the G.I. Joe brand, but Sunbow’s Tom Griffin, Joe Bacal, and Jay Bacal were reading his scripts and making comments. So too was Kirk Bozigian. Dozens of talented artists were visualizing Friedman’s ideas, staging, and dialogue into storyboards, backgrounds, and moving action. So in the sense that no one had written full G.I. Joe TV scripts, and he concepted what would happen in the first miniseries, and how we’d feel about it, and that we’d love the characters, absolutely yes, he created G.I. Joe. I know how good G.I. Joe was by comparing to similar shows, like He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, M.A.S.K., Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos. Each has its own bright spots, but none are as complex, fast, smart, or funny as G.I. Joe. Story editors like Steve Gerber and Buzz Dixon carried the Joes’ torch for 50+ scripts after Friedman, but Friedman started it. Did Friedman “create” the earliest G.I. Joe scripts? Yes. The franchise? Well, that was a team effort.

But let me get back to Friedman’s talent. Halfway through the Weather Dominator story, Spirit and Storm Shadow vie over the same piece of technology, trapped in a partially submerged cave. They fight to a standstill. Storm Shadow calmly accedes that “soon we will either use up what oxygen remains or the sea will rise and take our lives.” Spirit responds that “We must dwell on this,” and the two stop fighting, sit down, and close their eyes, the Weather Dominator fragment floating just next to them. That is an unbelievable piece of writing, especially for a kids cartoon in 1984!

In the following episode, Storm Shadow infiltrates Joe headquarters to steal a different Weather Dominator fragment, and except for three words, there is no dialogue for 58 seconds straight! The whole scene is told visually, with the ninja sneaking past Joe guards, climbing up a cool/weird glass column, zapping a hole in it, and lowering himself down with a winch. He-Man and M.A.S.K. were not not attempting this. And maybe it’s even unfair to compare Friedman’s killer writing on an animated series to other cartoon shows, because he certainly wasn’t thinking about other toy tie-ins. Rather, as someone who’d written The Dukes of Hazzard, Starsky and Hutch, Vega$, Charlie’s Angels, All in the Family, The Partridge Family, Gilligan’s Island, and more, he was thinking live-action.

The second thing that strikes me about Friedman was the back and forth between him and others over credit. There’s a bit of disagreement about his two motion pictures. In the case of G.I. Joe: The Movie, Friedman gets “Written by” credit, while Buzz Dixon, who cumulatively spent as much time writing and story editing the daily cartoon as Friedman, nets “Story Consultant.” Credits for Writers Guild-covered productions are particular entities.

Third is Friedman’s contribution to Transformers. As with G.I. Joe: The Movie, Ron Friedman wrote The Transformers: The Movie. Here Flint Dille was Story Consultant. If you know much about Hollywood, you know that narratives that complex with budgets that high are collaborative projects. (See below for even more on Transformers.) But I’ll refocus this paragraph away from named credits and towards story. The impact of Transformers: The Movie to my life cannot be overstated. As Robert Kirkman says in this week’s issue of Skybound’s monthly Transformers comic book, for an 8- or 9-year old growing up then, there is life before TF:TM and after. I mean, it’s the title of Ron Friedman’s autobiography! That would be I Killed Optimus Prime: Confessions of a Hollywood Screenwriter. And the film’s scale! One Sunbow person, of Friedman, said to me “He’d write these wildly imaginative… scripts…. The imagery was sometimes just extraordinary.” And having read Friedman’s earliest notes for Transformers: The Movie (and G.I. Joe: The Movie), for that matter, they are some of the craziest things I’ve ever seen in script-form.

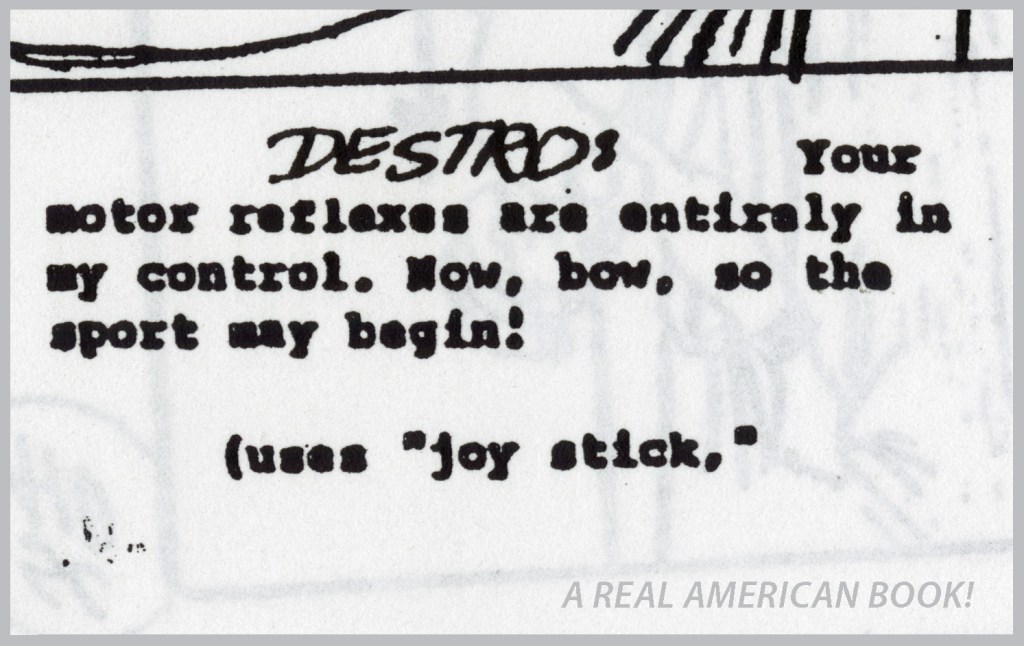

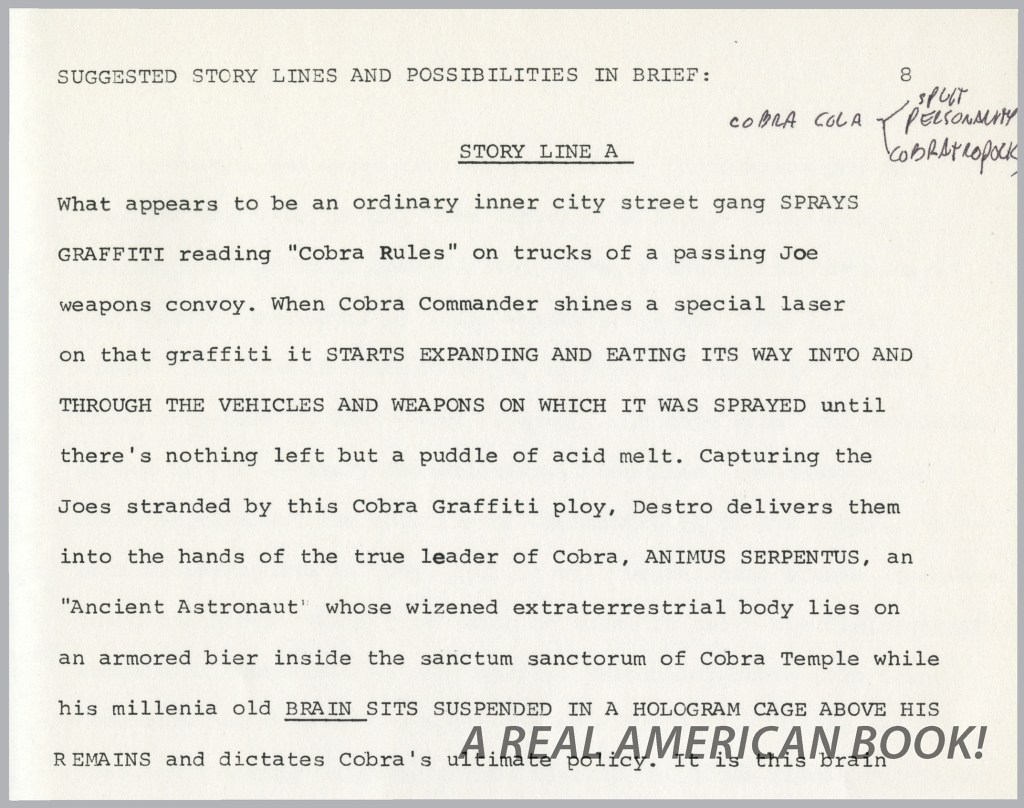

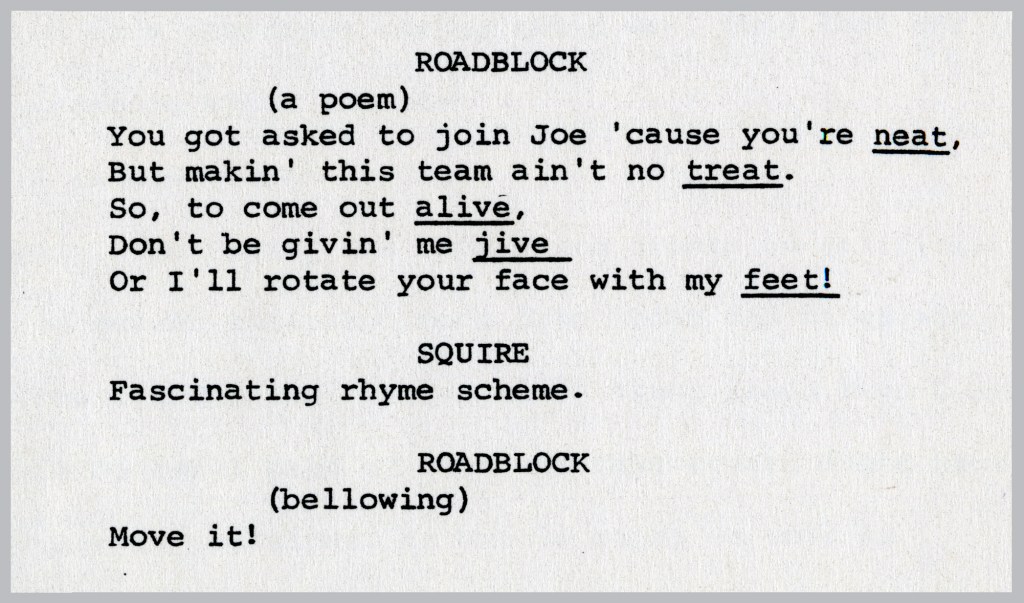

[Above: From Ron Friedman’s G.I. Joe: The Movie “More New Characters and Story Ideas,” dated May 31st, 1985.]

Ron Friedman interview excerpts

I spoke to Friedman by phone in June 2007. This is not an exhaustive career interview. I present this to give you a taste of how smart, thoughtful, and opinionated he was.

——–[begin interview excerpts]

RON FRIEDMAN: My background is, I’m an architect civil engineer, and I practiced for eleven years before I decided to follow my first love and write.

TIM FINN: Can you tell me about that transition?

RF: Well, I’d always written in high school and college and at Carnegie Mellon, Carnegie Tech when I went to it. I did four original musicals, one a year for the last four years of my five-year architectural class. And a lot of people, very famous in business, came out of Carnegie Tech drama school and Carnegie Tech period. [Lists Steven Bochco, Rene Auberjonois, and John Wells as examples.]

TF: Was there an epiphany or did someone important say, “You know, you should really just write”?

RF: No. It was my decision. And I’d always loved to write. And I’d always written and won prizes for it in high school and got good grades for it in college. I always enjoyed it. And I was practicing as an architect. I had two kids. I worked seven days a week with my own practice and I was the chief designer and job supervisor for a medium-sized Pittsburgh office. And I couldn’t clear ten grand a year. And I thought, well, I’ll try to write for television or motion pictures. That pays a lot better. And I always loved it.

So I sold my practice for, you know, ten cents and took a chance. And one of the reasons I did that is that a then famous comic, Shelley Berman, was going through Pittsburgh. I’d met him in summer stock when I was working there as a scene designer and actor. And I convinced him he remembered me and asked him if he would read some stuff I’d written. And he did and said, “Schmuck, come to New York and I’ll get you an agent.”

Well, I went to New York and he was leaving as I arrived, even though he knew I was coming. And luckily, my fraternity brother was then the scene designer for a very successful show, The Perry Como Show in New York. And he took me to the William Morris Agency — He took me to Goodman Ace who was the head writer of The Como Show. He read some of the things I’d written on spec. And he pointed to his writing staff and said, “If any of these guys die, I’ll give you a job right away. But I don’t have the budget for it now.”

So he called to one of the chief [agents? agencies? A noise on the line, missed a few words] came, said come on over and met with me and signed me up with the agreement that I’d move to New York. And that’s how it happened. I starved for the first portion of a few months. My wife came back to New York with the kids and I never looked back. My first year writing special material, which is comedy for stand-up comics, which is not what I planned to do, that first year in New York, I made almost five times my best year as an architect. That’s how it happened.

MOVING TO THE WEST COAST

TF: At what point did you move to Los Angeles?

RF: The Danny Kaye Show came and got me. I didn’t want to go to Los Angeles. I’d been in Los Angeles. I didn’t like it. I thought it was no place. I loved New York. I was doing very well there. I was doing comedy record albums, which were big business then. And I was in demand writing stand-up comedy. And very often the comics would say, “It’s not funny. You do it.” And I would do it and get big laughs, and then they’d have to pay me.

Anyway, I was working with Vaughn Meter, a name you may not know, but he was the guy who did the impression of John F. Kennedy and had a giant hit album called The First Family. And in it, he impersonated John Kennedy. It was a giant bestseller, I mean, double platinum, you name it. It was the record because Kennedy was beloved, he was beloved. So I was working with him. He did a second album that was equally successful. And I was working, writing an act for him where he would be impersonating President Kennedy. And I was with him the day Kennedy was assassinated. And he says, “Oh shit, what am I gonna do now?”

So anyway, what happened was, that time passed. And he wanted to go on with [his] career. He picked me to write his new act, first time he would do an act as himself. And I wrote his act, which was to open at the Blue Angel in New York, which was the comedy club. I mean, that’s where Barbra Streisand first achieved notice of meaning, and a lot of comics appeared there, and came out of nowhere to starve.

Anyway, because it was Vaughn Meter and he’d been the President or just as beloved as the President, all the media came to cover it, I mean, all the media. Time magazine was there, Newsweek. Then it was Look magazine. I mean, pick something, The New York Times, Chicago…[inaudible]. Every newspaper, all the television, they were all there to cover his new act.

Anyway, his new act got reviews in Time magazine and elsewhere. And the essence of all the reviews was that the material was brilliant, but that Vaughn Meter was an indifferent performer. It turns out that Perry Lafferty, who was then the producer of The Danny Kaye Show, saw it and made me an offer. And I took it, came out to the Coast with my wife and kids and–

Anyway, I hated the idea of being here [in Los Angeles]. I had to learn to drive, which I never needed to bother with in New York. And I never left.

TRANSFORMERS

TF: You’re credited for Transformers with “Additional Dialogue” in the regular episodes.

RF: [Griffin and Bacal] pulled me over to rewrite the first 64 scripts. That’s a lot more than sweetening. But, you know, they had made their deal with the writers. They didn’t want to give me ‘written by’ credit, ’cause some of the scripts I rewrote completely. Some of the others I punched up or polished. But that was the credit, yup. That would explain that.

TF: Do you have a sense of how many you rewrote completely versus just punched up?

RF: I’d say at least 50%. Or let’s say rewrote substantially, so as to make them more intelligible, funnier, and also bring the characters forward so somebody could tell the difference between them, because there were so many characters. I mean, it was really a parade of products more than anything else.

LOCATION

TF: When you interacted with [Sunbow Productions’ heads] Griffin and Bacal, was this all by phone and mail? You were in Los Angeles–

RF: They had an office out here, and I would see them whenever they were in town. They also put me to work on other things they had hoped to make happen. You know, they were really Hasbro’s ad agency, I guess, or some such designation. And so any time there was a new show in the wings, a hoped-for new show, they’d call me in. There were some things that didn’t make it that I thought sounded interesting initially. One of them was called Air Raiders.

I came up with a bible and with the characters and the way things interacted. And I wrote a pilot script or two, the bible for a series. But the toys didn’t work. And when I saw the prototypes of the toys, you know, I thought, “well, it’s only a prototype. It’s gonna get better.” Obviously it didn’t.

FRIEDMAN WAS IN DEMAND

RF: I was, you know, very busy. I was doing a hell of a lot of different shows. I worked in [live-action] drama and comedy and variety, and then animation. And I was in demand. So, I mean–

TF: And you wrote from home?

RF: Yeah, generally. Once and awhile the deal was to be a story editor. That’s a job I generally tried to avoid because I could make much more money writing freelance. But as ageism screws got tighter and I realized that I had to take what was out there, I did take some jobs as story editor. And then I would work, for example, at 20th Century Fox when I was a story editor on The Fall Guy and a couple other things like that. But I generally tried to avoid it.

TRANSFORMERS: THE MOVIE

TF: Did you go to a premiere for Transformers?

RF: I did. It was in Westwood and the thing that disturbed me the most was that the soundtrack blew the earwax out of a mummy’s ears. And it was impossible to hear the dialogue. And I commented on that. And Joe and Tom and… Jay, they weren’t too thrilled that I said that. But that’s what I felt. And subsequently, the soundtrack has been toned down so you can actually hear the dialogue. Oddly enough, I’d been teaching screenwriting at USC Film School for the last ten years. [Ron and I spoke in 2007.] And I also teach a summer seminar in screenwriting at USC for the last seven years, five days a week for the month of July for brilliant high school kids from all over the country and sometimes the world.

And they all love the Transformers: The Movie. And I am always asked several times a year to go sign DVDs and VHSs of that film. And sometimes the G.I. Joe movie as well, which it seems that most fans of the Transformers have also seen G.I. Joe: The Movie, and loved. And G.I. Joe: The Movie got a much better review in Time magazine and other things than did Transformers.

[But in Transformers,] I couldn’t hear 90% of the dialogue. And to me, if you can’t hear the dialogue, you’re missing the movie. I liked, you know, “You’ve Got The Power”. I thought that was great. But I didn’t like the fact that the soundtrack was then so goddamn loud that the dialogue was not hearable. And I noticed on the DVDs and the VHSs, it was toned down considerably so that you can hear the dialogue.

WRITING NOW AND WRITING THEN

TF: How has writing for movies or television changed in the last 30, 40 years?

RF: Well, there are fewer knowledgeable people present. That makes a hell of a difference in terms of the things that are attempted. That’s one of the reasons that reality television came in because there was such a boring sameness to the other programming. The reason there was such a boring sameness is that the people who were in the supposed creative slots at networks and studios were always attempting to duplicate the success of things that they’d seen before so that they could cover their ass. And if it didn’t work, they could say, “What do you want from me? This is just like The Mary Tyler Moore Show. What do you want from me? I got the same guys that did this,” or the same guys that did that.

So there’s been a sameness and a predictability that has periodically killed off any invention in the marketplace, which now seems to be largely to be found on cable and not on the television networks. And if it is on the television networks, the network brass no longer waits for a show to find an audience. They cancel it immediately.

And many of the most successful shows of all times did not and were not successful when they were first aired. Case in point, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, case in point, All In The Family, and a number of others, St. Elsewhere. I mean, there’s a big list. They didn’t really do well in the ratings for the first year or more. But the executives in charge believed the show was good, in some cases, for ABC particularly, nothing was working and they didn’t want to spend the money to put other things on that might even work more poorly. So they stuck with shows and they discovered, if their eyes were open, that audiences found shows and then learned to stay with them.

There were other lucky accidents that wouldn’t have happened if the show had been cancelled quickly. An example of that being Happy Days, because until Fonzie, the character of Arthur Fonzarelli came onboard, the show wasn’t making it. And if the show had been dealt with the way shows subsequent to that have been dealt with, which is cancelled if they’re not giant hits within the first episode or thereabouts, Fonzie would have never showed up. There wouldn’t have been all those years of Happy Days.

TF: Besides this lack of quality, has anything changed for the better in writing for movies or television?

RF: I’m thinking. Well, I like to think, and I’m not just making this up, that things, the quality was better, the professionalism was more outstanding, and the invention was greater when I was most active. The reason being, that there was an appreciation for quality and that there was a recognition that there’s an audience out there. I’m trying to think what’s better. Technically, there’s a lot of technical improvements. A great number of things are now possible to do for a price that were not possible before. But television has always been a copycat medium. Oddly enough, whereas television, because of its immediacy and its ability to cover news, should be where you could go to get updates on news and have stories about things that are happening now, except on cable, television doesn’t do that. Motion pictures, which have as much as a two-, three-, four-year delay before the movie gets out there, they seem to deal with more topical material more fearlessly and regularly than motion pictures do.

So, again, I’m searching for what’s better. I don’t think much. One of the reasons I don’t think much is because the executives that are in place mostly have to have good luck. If they have good luck, they take credit for everything that passed before them. If executives are replaced at any time during the season, on film and television, everything that was in development under his or her imprimatur is immediately squelched. ’Cause nobody wants something to be successful that came from the preceding administration. That to me is tremendously destructive. And it’s part of the ‘cover my ass’ mentality that’s now more deeply engrained than ever.

But to me, the biggest deficit is that too few of those in the position of buying or putting into development various projects for television and for film, too few of them have any sense of what a live audience will sit still for. They are couch potato babies. They are used to sitting in front of the television set and letting the laugh track tell them it’s good. Or they’re used to sitting in front of niche market cable shows which cater to their particular generation or interest and just luxuriating in the familiar. Which, in actuality, is nothing that a general audience has the least interest in. And that’s why so many television pilots that are made and series that go on the air don’t last, ’cause too few making them and fewer still who give the green light to the making of them have ever had to suffer an audience’s response to material that’s been prepared under their watch.

They don’t know what an audience will sit still for. They don’t know why people laugh or when. They don’t understand how it happens. And they’re not about to learn. And I’m not alone in thinking this.

——–[end interview excerpts]

Now it is 2025, and I wonder if Friedman’s take on the state of television had changed since we spoke. Certainly with the rise of streaming and a shift away from both network programming and cable, and with movies moving more to franchises, many viewers, reviewers have scholars have noted we’re in “peak TV.” I have a slight regret that in posting this interview excerpt here, I’m too concretely tying Friedman’s opinions to 2007. But interviews are more timely than timeless, and I’m not purporting this to be the final word on Mr. Friedman. You can find lots of interviews out there, and you can read his book.

It was a pleasure speaking with him, and I particularly can imagine what an engaging professor he must have been. It would have been fun to take his classes, to hear him talk about what goes into a good script, what makes a compelling character, and to write weekly passages for him to comment on and grade. My condolences to Ron Friedman’s family, friends, and many former students.

[Above: a bit from Friedman’s G.I. Joe: The Movie “story outline (expanded version),” dated July 1st, 1985. This predates the final screenplay by roughly seven months. Tons of ideas were proposed, changed, and dropped in that time.]

Had a fair few of his scripts come my way, not only both versions of TFTM, but also his largely built from the ground up treatment and outlines for Bigfoot and the Muscle Machines (which was then cut from 15 to 9 segments and handed over to Flint Dille).

The Sunbow Marvel Archive is an amazing resource!